|

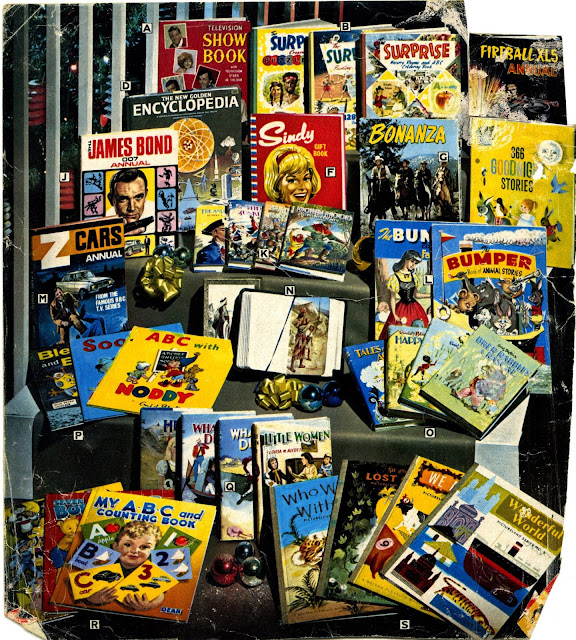

| Noggin the Nog is shrunken by a voltage reduction, September 1965 or thereabouts. (Image re-created in photoshop… but we had that exact GEC telly). |

Some of my earliest memories of

television are of it going wrong. Whether as the result of an

unaccountable break in transmission, voltage reductions, or simply a

valve blowing in the back of the set, breakdowns were enough of a

regular occurrence to seem like a normal part of the viewing

experience back in the 1960s. Most people of a certain age will

recall the various apology captions used by broadcasters when, for

whatever reason, there was an unexpected break in transmission. The

usual message was: ‘We apologise for the loss of your programme.’

This printed caption would sometimes be reinforced by a voiceover

from the continuity announcer, leading to the inevitable: ‘in the

meantime, here is some music.’

Commonplace as such interruptions were,

it was frustrating when a favourite programme fell victim to a

technical hitch. On the evening of Friday January 12th,

1968, my brother and I sat down to watch that week’s episode of

Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons, a story entitled ‘Traitor.’ It featured the

first (and only) appearance in the series of the Spectrum hovercraft,

the sabotage of which formed the cornerstone of the plot. The episode

had barely got underway when, just as an ominous jet of oil had begun

to spray forth from the doomed vehicle, the screen went blank. Beyond

this, I don’t recall the exact details of the breakdown, other than

that the episode did not resume: I have a vague idea that an ATV logo

appeared on the screen, and there was probably some kind of

announcement and/ or apology to the effect that the break in transmission was as a result of industrial action. Either way, there was no Captain Scarlet that day.

Forever after, my brother and I recalled this occasion as the

instance when ‘the technicians went on strike.’

There was to be a more serious strike

later that year, affecting ITV in the aftermath of the franchise

reshuffle of July ‘68 (the point at which our local weekend

broadcaster, ABC, ceased to exist). But whatever pulled Captain

Scarlet off air in January was most likely a local dispute. True to

form, the indestructible man returned to complete his interrupted

mission, over three months later, when the episode was finally aired

on April 23rd.

The Captain Scarlet breakdown was by no

means the first technical hitch I remember. From quite an early age,

I was aware that television sets were prone to breakdowns, and

have memories of an overalled engineer tinkering about in the back of

the set whenever a valve went west. When the set was fully warmed up,

the valves generated a fair amount of light and heat which could be

seen through the ventilation slots in the back. The light from inside

the set helped to reinforce the childish impression that there were

little people inside it, performing, and I still remember looking

through the slots during an edition of Sunday Night at the London

Palladium to see if I could spot a tiny Norman Vaughan...

The early valve-driven TV sets were

much more prone to breakdowns, but even in the era of the solid-state

colour sets, there could be problems: I well remember the green

complexion of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea’s Admiral Harriman

Nelson when one of the ‘colour guns’ in the back of our set went

on the blink... and an equally annoying – and seemingly incurable problem arrived with the dawn of televisions with hi-fi sound: the

magnetic field from the speakers on either side of the set was prone

to induce areas of false colour in the tube. I was reliably informed

that degaussing would cure the problem. Getting another set was

simpler: we rented until well into the 1990s. In an era when the

technology was so prone to developing faults, this was a safe bet, as the cost of any remedial work was immediately covered: although it could

sometimes mean going without the telly for a few days while the

repair was carried out.

An earlier and almost entirely

forgotten technical phenomenon affecting one’s enjoyment of

television was that of the voltage reduction. These step-downs in the

local supply were well known during the 1950s and 60s but nowadays seem to

have been completely forgotten, and are neglected in all commentary on

the early days of television. The sole

reference that I’ve been able to find is one made by Tony Hancock, who offered the voltage

reductions as an argument in defence of the poor ratings for his ATV series

broadcast at the beginning of 1963. ‘All the viewers could see on

their sets was a postage stamp-sized Hancock’, he complained to the

Daily Express.

My recollection is slightly different:

a ‘postage stamp-sized’ Hancock suggests a small, square picture

in the centre of the screen, which may well have been the case on

certain occasions. But the instance that I recollect most clearly

came during a Sunday afternoon broadcast of Noggin the Nog (a

check on the BBC’s Genome website suggests this to have been Noggin

and the Firecake, broadcast on Sunday evenings during September

1965). During the transmission, the picture began to shrink... almost

as though it had been affected by an evil spell from Nogbad the Bad.

But rather than diminishing into a small postage-stamp sized image,

the shrinkage affected only the height of the picture so that, after

a short time, the end result was as per the image I’ve re-created

above. No amount of adjustment to the horizontal hold would cure the

problem, and this was by no means the only occasion on which it

occurred. Aside from that Hancock reference, I have never come across

anyone who remembers this happening, but happen it most certainly

did...

Since the dawn of home video, technical

breakdowns are occasionally preserved for posterity, as this clip of

Star Trek from January 1985 illustrates. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P8xLEl_Uh1Q And even in today’s

slick digital era, it’s not unknown for a station to drop off the air

completely for no apparent reason. But the 1960s and 70s are my

remit, and as far as I’m concerned most modern telly can happily

disappear off air forever...