16-22 May 1970

Any vintage edition of the Radio Times or TVTimes is an intriguing snapshot of the era in which it appeared – not merely for what it tells us about the televisual content of the week in question, but the wider context provided by advertising, editorial and the inevitable letters page. This one, featuring the boardroom/oil exploration drama The Troubleshooters on the cover, turned up recently on ebay for a very reasonable £8 (good quality RT copies are usually listed at upwards of £15). So what, if anything, does this random edition reveal about life in Britain in the spring of 1970?

Radio Times had undergone a facelift in the autumn of 1969, replacing its austere block-serif title font with the fancy swash caps that would endure, with modifications, for over thirty years. To modern readers, this 52-year-old example would feel strangely cheap, printed for the most part on newsprint pulp, with only the covers and four internal pages in colour, on a dull, matt coated paper (TVTimes used this superior stock throughout the whole magazine).

The Troubleshooters was the biggest new thing that week on the BBC, and accordingly scores another cover (there had been at least four previous examples during the 1960s). The series was taking over the Monday evening 9.10pm slot from which Doomwatch had exited with a bang (non nuclear) the previous week. In common with most videotaped BBC drama of the period (and a fair amount of comedy), The Troubleshooters is mostly missing from the archive. Taking its lead from ITV’s immensely popular boardroom drama The Power Game, the series played off the management shout-outs against sweaty dramatic action ‘out in the field’. Many episodes sound intriguing from their plotlines, but it’s safe to say that its arctic or desert settings would mostly have been realised in the studio. Like its timeslot predecessor Doomwatch, The Troubleshooters followed the standard BBC drama production formula of filmed sequences inserted into a mostly VT studio-based production, and this 1970 series was its first year in colour. The Troubleshooters endured into 1972 when, along with Doomwatch, it passed into history. Despite having scored the RT cover this week, the series did not make the ‘big colour feature’, usually placed towards the back of the magazine. This week, it was given over to a new ethnographic BBC2 series The Family of Man, contrasting lifestyles in New Guinea and 1970s Britain.

On the reverse of the cover we find an advert for the ‘Baxi Bermuda Plus’, a gas fire with back boiler (a popular combination at the time). Mid-May may seem a strange time to be promoting such a product, although it was clearly aimed at far-sighted householders who would get their central heating systems fitted during the summer months in order to be ready for the autumn and winter (we certainly did in our house). There are only two other colour ads in the magazine, both aimed at the same demographic: the inside back cover promotes Axminster and Wilton carpets (which look pretty much the way you’d expect a carpet to have looked in 1970), while the back cover splashes Sanderson wallpaper, also looking determinedly of its time.

Editorial content includes a feature on the famous Harlem Globetrotters, who were appearing that week at Wembley as part of a world tour. ‘We try to strike a balance between comedy and basketball’ said their manager George Gillette. Quite how that worked out is hard to imagine, although fancy ball-twirling and nifty footwork probably played a part. The team would be turned into a comedy cartoon series by Hanna Barbera, airing from September 1970 in the USA, and debuting on BBC1 a year later.

The following page focuses on Henry Darrow from BBC2’s High Chaparral series, whose interview shares a page with Bery Reid, appearing that week in a production of Sheridan’s The Rivals on BBC1. The mere idea of BBC1 airing an 18th century comedy of manners at prime time on a Sunday night says a lot about where the Corporation saw itself in 1970 and how far it has come (some may say sunk) since then… The same page also provides a tiny boxed-out corner highlighting the week’s pop and jazz music, including appearances from The Move, Fotheringay, The Soft Machine and, er, Sweet Water Canal (of whom the internet has nothing whatever to say…)

Page 10 looks at that week’s edition of The Wednesday Play – another indicator of where the BBC stood on drama at the dawn of the 70s – but somewhat more interesting is a coupon inviting younger viewers to vote in Jackanory’s ‘hit parade’: a chance to nominate favourite tales for a repeat run. The stories and their narrators provide a neat snapshot of the state of play chez Jackanory during this ‘classic’ era. I’m sure I saw all of them. Across the spread, what we must take for a typical 1970 housewife (resembling a less scary Mary Whitehouse) extols the virtues of her ‘Creda Autoclean’, an oven that, no kidding, actually cleans itself. Well, it was the seventies after all…

As I mentioned in the intro, it’s the adverts as much as the TV listings that add period colour to these vintage publications (albeit most of them are in black and white). Page 13 is given over to the ‘McVitie’s Treasure Trail’, with entrants invited to find the shortest way through a graphic maze for the chance to win prizes. Star prize was ‘a car for ten years’. No slouches, McVitie’s. The lucky winner would receive a Ford Capri 1600 GT, fully taxed and insured, and replaced in subsequent years with ‘its equivalent’ (presumably another Capri – the marque endured until 1986). Of course, you needed to eat some biscuits if you wanted to enter: ‘treasure tokens’ were included on special packs of Jaffa Cakes, Chocolate Homewheat, Rich Tea and Digestive (all of them still with us 52 years later). And while you were munching your way through that lot, you could be giving some thought to completing the obligatory slogan ‘McVitie’s Bake a Better Biscuit because’ (in no more than 12 words).

Page 15 features the Kodak Instamatic camera. I always got this confused with the Polaroid Land ‘Instant’ camera, but this was of the conventional point-press-take-the-film-to-Boots variety. The layout of this ad is a classic example of ad agency art directors’ work of the era, and it would be hard to improve on its clean lines today. Other advertisers include Gordon’s Gin, ‘New Calor Gas’ (propane cylinders providing a domestic gas supply), Lurpak butter, Diamond Paints and the nursing profession. Most redolent of the moment, on page 34, is a reminder to collectors of Esso’s ‘World Cup Coins’ that they still had time to complete their collections. These 10p piece-sized items commemorating that year’s England team players were given away at petrol stations at a rate of one coin for every four gallons. In 1970, a gallon of petrol cost six shillings and eightpence, so to qualify for a coin, you had to spend… well, you work it out (just a bit over £2). Adjusted for inflation, that six shillings and eightpence would be equivalent to £4 today, so each of those neat little coins would be setting you back £16. Of course, you also got a Tiger in your tank… but could you find Peter Bonetti?

So much for the commercial world, but what could consumers look forward to watching on the box when they weren’t eating biscuits, decorating their houses or filling up their Ford Capris? BBC television in 1970 consisted, of course, of just two channels, both now broadcasting in colour. Saturday’s programmes began at 9.35am with a raft of language courses lasting until 11.0, when the service closed down again. It was back at 1.10 with Jack Scott providing the weather forecast (almost certainly thunder… it was thunder all the way in May 1970). This led into the inevitable Grandstand, introduced by the inevitable Frank Bough. That took care of the whole afternoon until 5.15 when Dr. Who ushered in the evening’s entertainment with the second episode of Inferno. Evening highlights (I use the term in its loosest sense) included Dad’s Army, an adventure movie (Many Rivers to Cross), A Man Called Ironside and… oh dear. Page 18 reveals a photograph I dare not reproduce, promoting that evening’s edition of The Black and White Minstrel Show. Unbelievably, this dodgy old chestnut still had another eight years to run on air before continuing as a holiday camp entertainment until – gasp – 1989! I positively hated the B&WMS. Not because I was developing a precocious politically correct sensitivity at the tender age of nine: I just detested all that dressing up and poncing about whilst singing ‘Polly Wolly Doodle’… Of course, you could always turn over to BBC2 where Chronicle presented a film entitied ‘One People between the Alps and the Sea!’ followed by The Young Generation. Fortunately, there was good old ITV to fall back on.

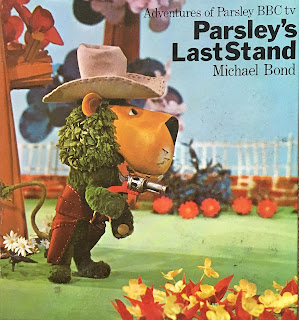

Sunday’s big hitters were Paul Temple on BBC1, and the aforementioned The Rivals; whilst BBC2’s line-up included Rowan and Martin (a scheduling fixture at the time), and what sounds like the 1970 equivalent of Coast – Bird’s-Eye View, an aerial tour from Montrose to London. Monday on BBC1 gave us Star Trek – well into its second BBC season, with Wolf in the Fold – along with The Troubleshooters at 9.10 and The Harlem Globetrotters at 10.00. Over on BBC2, the dreaded Pot Black was probably being recorded over last week’s Doomwatch. This isn’t as insane as it sounds: colour videotape was expensive, and routinely re-used after wiping. The entire 1970 series of Steptoe and Son, the first in colour, is known to have been sacrificed to the tedious snooker fest. Elsewhere in the same week, we find Z Cars now in its 2-part ‘soap opera’ era (best ignored), a forgotten spy drama series Codename on BBC2 (almost certainly wiped), medical soap The Doctors, eccelsiastical comedy All Gas and Gaiters, plus such schedule staples as It’s a Knock-Out, Sportsnight with Coleman, Man Alive and Tomorrow’s World. Curiously, a Frank Sinatra concert – which to me seems like a televisual big deal – was tucked away at 9.10pm on Wednesday on BBC2. Wednesday also saw Marius Goring starring in the popular forensic drama The Expert, whilst Friday night’s big 9.10 pm drama was a repeat run of the hugely popular The Forsyte Saga (made in black and white, this would be its last sighting on terrestrial television). In the head-scratching category comes Friday’s mid-evening comedy, The Culture Vultures, a totally forgotten comedy of business manners starring Leslie Phillips. Children were offered the likes of Banana Splits and a repeat run of Belle and Sebastian, alongside the ubiquitous Blue Peter. Occupying the prime slot ahead of the early evening news was Michael Bond’s Herbs spin-off The Adventures of Parsley. Parsley could also be glimpsed in cowboy guise on page 60, in a half-page promo for BBC books for Children. On the evidence, Parsley’s Last Stand looks like a must-have (a fine vintage copy will set you back £18, or six shillings if you own a time machine).

We’re almost done with our random week in May 1970, but there is still the letters page to consider. An attitude seems to prevail here, and it will be familiar to anyone who listens to Radio 4’s Feedback. Programme makers, taken to task over various aspects of content or taste will always defend themselves and explain why their creative or production decision was the only one possible. It’s rare for anyone to hold up their hands and admit to an error of judgement. In this issue, a reader takes Doomwatch to task for scientific inaccuracy in presenting a plastic-eating chemical as a ‘virus’, and for claiming that ‘fear of weightlessness’ (y’what?) is a symptom of paranoia. Series co-creator and scientific advisor Dr. Kit Pedler was having none of it, insisting that the fictitious plastic-eating ‘virus’ had been ‘tailored’ (but it’s still inorganic, so technically not a virus, a point he chose not to address), before going on to defend the other accusation, levelled at the episode Re-Entry Forbidden, whose script he claimed had been verified by ‘a group of psychiatrists’. Well, okay, Dr. Pedler, if you say so.

Sniffiest response of the week goes to the producer of Junior Points of View, answering a complaint that the viewers’ letters on said programme were dealt with so quickly as to be rendered unintelligible. ‘I suppose,’ writes a smug Iain Johnstone, ‘intelligibility can only be assessed subjectively.’ That’s telling you, T.A. Ayre of Bournemouth!

And finally, the award for most laconic reply of the week goes to John Howard Davies, producer of All Gas and Gaiters. ‘Do the ecclesiastics… exist in such a rarefied hierarchical atmosphere that they never encounter a solitary parishioner…?’ asks J.A. Timothy of Flint. ‘Yes,’ says Mr. Howard Davies.