Christmas '74

Christmas 1974 – I can remember it in some detail. Not like it happened yesterday, but with reasonable clarity considering it was fifty years ago. Strange how the memory works – I can picture us driving out to see our relatives on the afternoon of Christmas Eve; I can even remember the kind of day it was, the sky typical for the time of year, partly blue, partly cloudy. We were passing Hams Hall Power Station on our way to see a couple of aunts and uncles who lived in that general direction, and the radio was playing in our dad’s Austin 2200. I can even tell you the record that was playing: Gloria Gaynor singing Never Can Say Goodbye, number 25 in that week’s top fifty. Why this particular moment should have become lodged in the memory I have no idea, as the rest of the afternoon is a blank...

Reconstructing the past is always easier if you have a diary to refer to. My ‘Letts’ Schoolboys’ Diary’ of that year is small, and short on detail, except for when it comes to television, but there’s just enough there for me to piece together a run-down of the days leading up to Christmas 1974. On Thursday 12 December, I went to a Christmas concert at my old junior school. On the following day, we put up our Christmas tree – for more on that see day 2 in this advent calendar. On the evening of Saturday 14 December, we put up paper chains, during Bruce Forsyth’s Generation Game – and I can still picture us doing it. In fact, decorating the tree during the Generation Game would become a bit of a tradition in our house during the mid-70s.

|

| Christmas week 1974, as recorded in my Letts' Schoolboys' Diary |

The following day saw me back on my comic creating activities, which I’ve written about recently, breaking off only when an old school friend came round to play guitar. On Monday night, I watched that year’s edition of Carry On Christmas, ITV’s annual festive version of the famous film series. Four decades later, I designed a sleeve for the DVD release. Wednesday’s big event was the coming of that year’s Christmas TV and Radio Times, the latter featuring Frank Spencer on a decidedly austere and mostly un-festive cover. Tommy Steele was on the TV Times, an issue sadly missing from my collection of pdfs. If I could spare the £54.99 the seller is asking for, I could have got the same ATV Midland edition off eBay in time for Christmas… albeit fifty years too late.

The following evening was the night of our school carol concert, and I was in the choir so attendance was inevitable. It’s solely on account of rehearsals for said concert that I know how to pronounce the word ‘excelsis’ which appears in the lyric of Ding-Dong Merrily On High. Back in primary school, we’d sung it the way it looks – ‘ex-sell-sis’ when in fact it should be pronounced ‘ex-chel-sis’as any Latin scholar would tell you, and our music master insisted. That’s very Boris Johnson of me, I know...

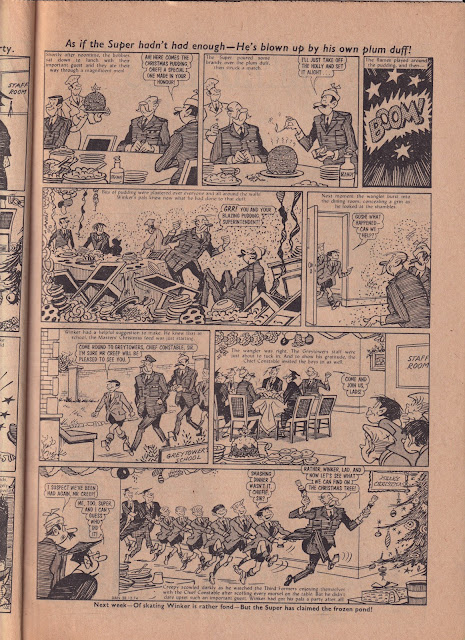

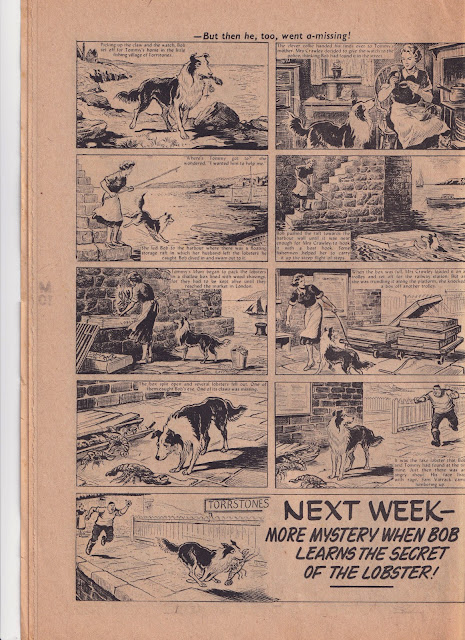

The following day, Thursday 19 December, we broke up for the holidays, giving us almost a whole free week to get ready for the big day. On the Friday evening, we got a repeat showing of last year’s Goodies and the Beanstalk, which was very welcome. On Saturday, I bought my mum’s Christmas present, seemingly from a discount warehouse called ‘Big D’ – the diary does not record what it was, but in the words of Bob Ferris from that year’s Likely Lads, it was almost certainly ‘something for the house’. I also got the Christmas edition of The Dandy, which you can share by scrolling down.

On Sunday, as I’ve mentioned previously, the evening’s must-see television event was the BBC’s Omnibus profile of the careers of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, a film that would be well worth resurrecting. On Monday 23rd, the BBC gave us another excellent documentary in the form of Horizon: How on Earth Did They Do That? (9.05pm, BBC2) a film that went behind the scenes of the movie special effects industry and included rare clips of scenes censored from King Kong, as well as a tantalising first glimpse of Gerry Anderson’s Space:1999. As if that wasn’t enough, by turning back to BBC1, if you could endure The Spinners at Christmas, you’d have been rewarded with the first broadcast of what was arguably the best of the BBC’s Ghost Stories for Christmas – The Treasure of Abbot Thomas (11.35pm, BBC1).

Christmas Eve was a Tuesday – then as now – which meant a new Top 20 at lunchtime. Following this, we went out for the afternoon, which is where I started this reminiscence. We were back home in time to see another festive first, the ‘Special Edition for Christmas’ of Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads. I’ve seen it so many times over the years, it's hard now to imagine it as a brand new programme. It will, unfortunately, never be broadcast in its original form again, the BBC having excised a line in which Bob namechecks the dread bearded antipodean entertainer. The episode ended with the characters having a ‘Christmas drink’ and I did the same thing myself as soon as the programme was over. Mine was a scotch and dry ginger, which was something of a watershed moment, as I believe it was one of the very first times that I drank spirits (I was just thirteen). These days, I’d pass on the dry ginger. With this in hand and a bowl of nuts on the table, I sat down to enjoy the evening’s big film, Ice Station Zebra.

Christmas Day brought a visit from our Grandparents – from 1967 until 1972 we’d been to their house at Christmas, which meant leaving all our new toys behind for the day when we’d only just opened them. A falling out between relatives had brought this to an end in 1973, and this year the roles were reversed. As to this year’s ‘toys’, for me, that meant a lot of LPs – three Beatle albums, a James Bond Collection, Eric Clapton’s recent 461 Ocean Boulevard, 10cc’s Sheet Music, an EMI Dracula album and, incongruously, an LP by the year’s chart-topping band Paper Lace. The latter is possibly on course for some kind of record, as it has never seen turntable action from that day to this. On top of all this, I got a Polaroid Camera – why I didn’t ask for a proper camera, I’ll never know. I think I liked the idea of getting instant results, but I was several decades too early for a smartphone...

Boxing Day meant a Beatles film, and as we’ve previously seen, this year’s offering was a second outing for Help! It may have been in colour, but it looked like an artefact from another time, for all that it was a mere nine years old… a few months older than the album Rubber Soul (originally released just in time for Christmas 1965), which I played for the first time that same afternoon. It was darkly overcast outside, and like that Christmas Eve car ride, I can still replay the scene in my mind’s eye. Hearing Rubber Soul was little short of a revelatory moment. I already knew the Beatles were good, but I didn’t know they’d ever done anything this good. The progress they’d made in the few months between this and Help! was phenomenal. It was the best LP I’d ever heard. It still is.

By 1974, Christmas on BBC1 meant a complete Dr. Who adventure, and this year’s offering was Planet of the Spiders, nicely edited down from the unweildy 6-episode original to fill an hour and forty five minutes on the afternoon of 27 December. Planet of the Spiders was the first regeneration I’d ever witnessed in Dr. Who, so it felt a bit special. The scheduling was deliberate, for the following day would see Tom Baker make his debut in the role.

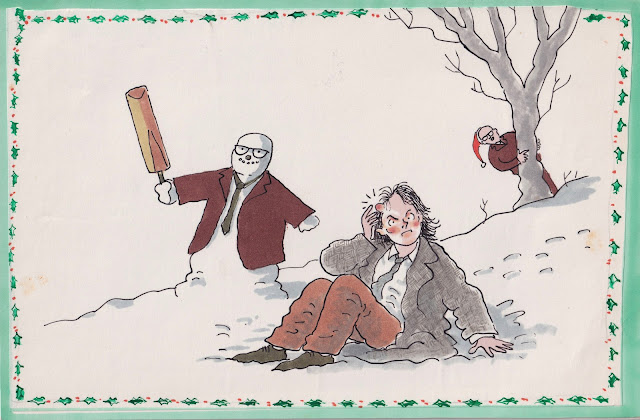

The rest of the festive season was spent drawing nonsensical cartoons, playing games we’d been bought at Christmas (‘Spy Trap’ [above]– a kind of tiddlywinks with attitude) and playing with toys. I know – I was thirteen, surely I’d grown out of Lego by this time, but no. I may have been still of an age to play with toys, but I was old enough by now to be allowed to stay up and see in the New Year. This was no big deal in our house – our Dad was always out on a gig on New Year’s Eve, traditionally the best paying night of the year for any musician, so we didn’t do anything special. Instead, we saw a bit of The Old Grey Whistle Test, now well on its way to becoming a New Year tradition. New Year’s Day, a bank holiday for only the second time, brought a random repeat of a UFO episode (The Psychobombs), more Lego fun and a visit to our grandparents. There were still six more days remaining of the school holidays, which came to an end in style with a visit to the cinema on Monday 6 January to see a James Bond double bill – Live and Let Die and the nicely festive On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

And with that, we were done. Whatever you’re up to fifty years later, have a very happy and peaceful Christmas and I hope you’ve enjoyed this nostalgic trip down an artificial snow-lined memory lane. Sunday – in even older money – will resume normal service in the year 2025. Which I think should be the cue to end on a song…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=izQB2-Kmiic

And here's that Christmas Dandy – in full – click on each image for a larger version.