|

| They were the Village Green Preservation Society – the Kinks. L-R: Pete Quaife, Ray Davies, Dave Davies, Mick Avory |

I recently met the author of this small

but informative book about the album The Kinks are The Village Green Preservation Society. The venue for this encounter

was a symposium on the subject of 60s film, and, specifically, the

question of where 60s pop culture belongs in the 21st

century. Not surprisingly, there was a lot of love for the Kinks, and

having spent more than a decade masquerading as Ray Davies in a Kinks

tribute, I drew on this experience myself in considering the subject

under discussion.

The band in question – Kounterfeit Kinks (look us up on facebook) – had played a mere handful of gigs

when, in the autumn of 2004, we performed at a rather fusty hotel in

Ashby de la Zouche. The band, playing in a

small and under-patronised bar, was barely getting through to an

indifferent audience, when in strolled a trio of guys who looked to

be around nineteen. These three then proceeded to make more noise

and show more appreciation than the rest of the audience put

together, and collectively, saved what would otherwise have been a

disastrous gig. Afterwards, thanking them for their appreciation, I

asked how it was that guys their age were so into a band like the

Kinks. The obvious answer: they’d been plundering their parents’

record collections.

We’ve all done it. My own musical

education started the same way; only back in the early 60s, it was

the likes of Frank Sinatra, Harry Belafonte and the Dave Brubeck

Quartet that made up the bulk of my parents’ small collection of

vinyl. I’d go a little further and suggest that the paucity of good

new pop groups in the early 2000s (a dearth that continues to this

day) is probably what sent those teenage guys trawling back through

their parents’ record collections. So much for Philip Larkin’s

assertion about parental influence...

Measured in terms of chart success and

popular appeal, the Kinks were a spent force by the time they

released the Village Green Preservation Society album. Yet

this, above any of the band’s other efforts, is the title most often name-dropped by other artistes, reviewers, and cultural

commentators. When it came out, in 1968, it pretty well failed to

register. But its themes of preservation, memory and nostalgia, are

exactly what set me to writing this blog; and I think they’re also

the reason why the album has gained so much of a retrospective

reputation.

I’m writing these musings for the

same reasons that drove Ray Davies to compose many of the key tracks

on TKATVGPS... as he says in ‘The Last of the Steam Powered

Trains’: ‘I live in a museum... so that’s okay.’ (You haven’t

seen my front room. It’s a shrine to old toys and vintage

guitars.) Ray, of course, is delivering a more complex, duplicitous

message as Andy Miller outlines in his discussion of the album. He’s

having his nostalgic battenburg and eating it: delivering a caustic

dismissmal of the efforts of mid-60s blues revivalists, yet doing so

in an almost spot-on genre pastiche, complete with riff-references to

Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Smokestack Lightning’, itself the source DNA

for the whole blues revival.

Those bands that Ray was having a dig

at – Alexis Corner, Manfred Mann, Stones et al – were, in their

own way, doing exactly the same thing as those three guys who saved

the evening in Ashby de la Zouche: digging back into recent musical

history in search of inspiration. Whatever Ray Davies’ ambivalent

thoughts about blues revivalism, it’s still an aspect of

preservation, although in the album’s title song, he puts this into

perspective: ‘preserving the old ways from being abused/ protecting

the new ways for me and for you.’ Holding onto the present whilst

acknowledging the importance of the past.

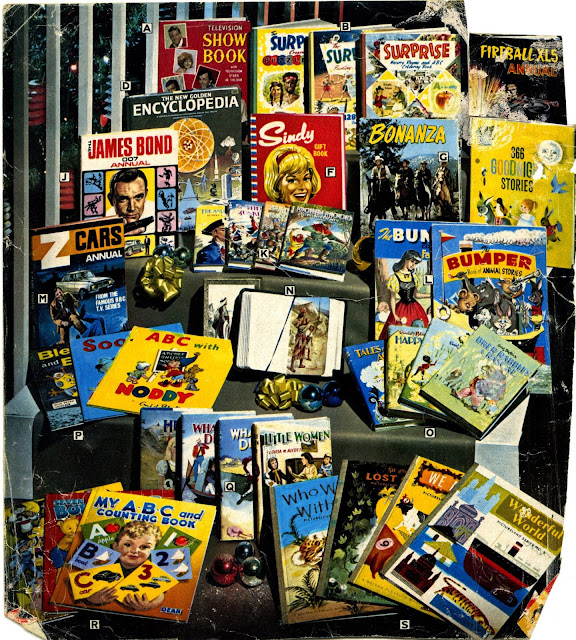

What I’m getting round to here is the

importance of artefacts: the old diaries, volumes of the TVTimes,

comics and toys that I’ve drawn on in writing these musings are

direct physical links with the past. Our parents’ record

collections are a link with an even earlier time; but as long as

those artefacts are available for inspection, the past will continue

to live on through popular culture, and, we hope, attract new generations of enthusiasts.

At that same symposium mentioned above,

I was asked how a company like Network (my employers) can continue to

find a new, younger audience for some of the archive titles we

release. Having considered the question, I’ve reached the

conclusion that we’re already doing something significant simply by

creating physical products of neglected and forgotten TV and film

titles. I’m not sure what the rate of decay of a DVD might be, but

I think (at least I hope) it’s a safe bet that they’ll still be

around, and in a playable state, in a couple of generations from now.

It’s far easier to imagine some child of the future picking up a

DVD boxset in their grandparents’ bedroom than it is to imagine

them scrolling through the contents of grandad’s hard drive. Even

if those DVDs are, by that time, unplayable, I’d like to think that

the packaging alone might be enough to spur them on to further

investigation... in much the same way as I have often been tempted to

investigate some otherwise unknown film, book or album simply because I

liked the sleeve.

As a sleeve designer, of course, I

would say that...