|

Late summer and early autumn was always

a time of excitement back in the 60s and 70s. Never mind the

inevitable return to school in September – this was the time of

year when the annuals began to appear in the shops. I always awaited their appearance with eager anticipation, perhaps for the simple fact that annuals

equalled Christmas and were, as a rule, the first potential Christmas

presents to appear in the shops.

Sometimes, one was afforded a glimpse

of them even sooner, via the pages of gift catalogues from Grattans,

Great Universal and the like. The autumn/winter editions of these

(now highly collectable) tomes generally turned up on the doorstep

towards the end of the school summer holidays, and the toys section

was invariably located towards the end of the book, followed by

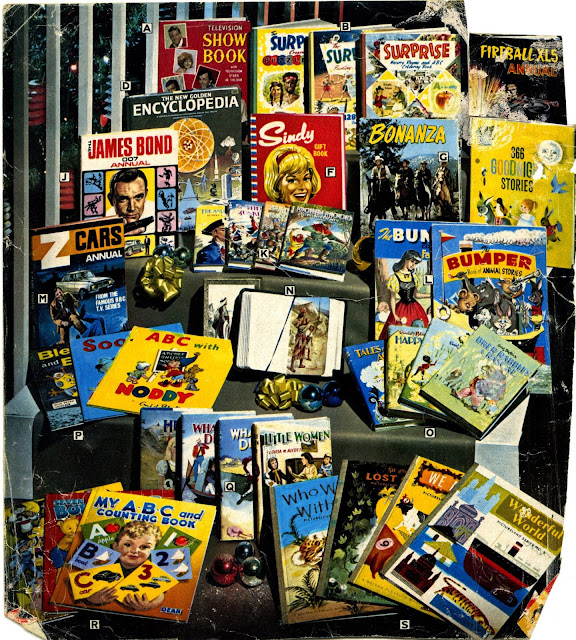

bicycles and camping gear. By chance, a page from a 1965 edition has

survived down the years, through having been glued into a scrapbook

later in that decade. Here, on display, was a selection of that

year’s annuals alongside storybooks and a few improving classics

(which were of no interest to me).

Such catalogues (or ‘club books’ as

they were known in our house) would have been in preparation since

the early part of the year, and it’s a safe bet that most of the

annuals in this line-up are dummies. If you look closely at the Z

Cars Annual, you might be able to see that the cover is a

printer’s proof wrapped around the previous year’s red-covered

edition in the manner of a dust jacket. The cover is evidently a

studio mock-up, for although the same painting appeared on the final

edition, the graphics were somewhat different, garish tones of red

and yellow being substituted for the more subtle orange, white and

black on show here.

Of this selection, I ended up with

Fireball XL5 (though I liked the look of Z Cars and

James Bond), as well as the slim Bleep and Booster book.

Fireball XL5 Annual was a regular Christmas present,

and always came courtesy of my grandparents, in a somewhat charming

family tradition. The run of four Fireball XL5 annuals came to

an end in 1966, which was coincidentally the last year that we spent

in our first home, before moving on. That last edition, therefore,

came to symbolise the end of an era.

Compared to what passes for children’s

annuals in this day and age, these were weighty tomes indeed.

Collins’ Fireball XL5 and Supercar titles came in at

96 pages each, and, with a few minor variations, followed a set

format that combined limited colour pages (beginning, middle and end)

with black/red spot colour and plain black printing. Colour pages

were printed on a lightly coated stock, while the remainder were on

heavy pulp. There were no photographs, and this tended to be the case

with most annuals from the 1960s, with just a few titles managing a

photographic cover such as the one seen here on Bonanza.

Inside, photography, in the few editions in which it appeared, was

generally limited to endpapers and title plates or, as in the case of

the Dalek annuals, centre sections. Until 1966, such interior

photographs were almost all reproduced in black and white.

Compare that to the slick, all-colour

pages of modern annuals, which generally come packed with

photographs, and it may look as if today’s kids are getting more

for their money. But I’d argue that they’re getting less. The

annuals of the 1960s may have been churned out by the truckload, but,

in most cases, it was quality churning.

Annuals were always the poor relations

of their comic counterparts, and those produced to tie-in with TV

Century 21 are a good example of this trend. The big-name artists

were tied to their desks (one suspects literally in some cases)

turning out colour spreads, and were thus unable to contribute to the

production of the annuals. Only a few of TV Century 21’s

weekly contributors made it into the annuals, most notably Ron

Embleton (on the covers), Jim Watson and Ron Turner. For the most

part, the contents came from the pens of lesser, though occasionally

interesting talents.

The first TV Century 21 Annual

was somewhat of a disappointment to me when I tracked down a copy in

the mid ’70s. The printing was harsh, with sour tones of blue, pink

and yellow predominating, the colour being applied pre-press to black

and white outline artwork. I recognised the artwork of Desmond

Walduck from the same year’s Fireball XL5 Annual (which

incorrectly credited him as ‘B. Walduck’), and the tight,

cross-hatched work of Rab Hamilton; but none of the other artists was

familiar to me.

Later years saw an improvement, and the

addition of colour photographs, which added greatly to the appeal of

the TV21-based annuals, as did the change to a larger format

(commencing with the Thunderbirds and Lady Penelope

annuals printed in 1966). The colour printing of the stories,

however, remained bizarre, and seemed to have been airbrushed almost

at random onto overlays corresponding to the process colours of

yellow, magenta and cyan. This combined to give a smery, imprecise

effect, with colours spreading across the edges of the black and

white line work in a unique, but not very professional manner.

World Distributors’ titles also cut

corners in the production process, opting for a similar technique,

whereby areas of colour (and Ben Day dots or similar screening

effects) were daubed onto overlays. In fact, of the annuals I encountered

during the 1960s, the only ‘proper’ colour printing (ie. full

colour artwork photographed into colour separations) was in the

Fireball XL5 and TV Comic Annuals, along with a handful

of nursery titles such as the sumptuously-produced Teddy Bear.

As a consumer of these artefacts, I

knew which ones I preferred. Fireball XL5 was, to me, a cut

above the others purely in terms of the quality of artwork on

display. Eric L. Eden, a former Dan Dare alumnus, contributed

most of the illustrations to the first two, and his absence was

sorely felt in the later editions. Eden was, in fact, the very first

comic strip artist whose work I could put a name to (although Gerry

Embleton and Gerry Wood were also present in those early editions,

and it was a simple process of elimination to work out who had done

what). Eden, critically, signed most of his airbrushed endpapers (and

one of his three covers), so it was his name that I associated with

quality renderings of Fireball XL5. This was the kind of artwork I

aspired to produce myself. I’d never heard of an airbrush, but what

the hell? When I drew my own Fireball XL5 comics, it was Eric

Eden’s artwork that I used for reference.

Looking back with a more critical eye,

I can see now that Eden’s figure work was not as assured as that of

his former mentor, Frank Hampson, and the pages he later produced for

TV21 had a rather plain, naive look about them, with extensive

airbrushing replacing his former penchant for detailed cross-hatching

(as evidenced in the early Fireball XL5 and Supercar

annuals). But back in the mid 60s, I had found my first comic strip

hero. Were it not for his involvement with Dan Dare, Eden

might have been utterly overlooked by collectors, but even so, his

work remains criminally under-appreciated outside of the Dare

fraternity. He died young, not particularly wealthy, and in relative

obscurity, some of his last comic efforts being Dan Dare

strips for a couple of 1970s Eagle annuals.

Annuals remained a Christmas (and

occasionally autumn) tradition for me right through to the late 70s,

with The New Avengers and The Sweeney being amongst the

last I acquired. By this time, a new name had appeared on the scene,

Brown Watson, whose publications showed a marked improvement in

quality over what we’d been getting from World Distributors and

City Magazines.

Just a few days ago, with this blog

entry already in progress, I happened to find myself in the former

‘mecca’ of Annual production – Norwich. I’d always noticed

the ‘Jarrold and Sons’ printing credit on the title plates of

Stingray, TV21 and others, and wandering through the

narrow city streets, I came upon a department store of the same name.

Surely there must be a connection with the company that had printed

so many annuals? A quick Google search revealed that it was indeed

the same company, or a division thereof. Jarrold and Sons was, in

fact, founded as far back as 1770, in Woodbridge, Suffolk, moving to

Norwich in 1823. Although the publishing division was later sold on,

Jarrold remains a thriving independent retailer, with its department

store and other specialist shops (including a very nice art shop)

still an important part of Norwich city centre. In these days of

corporate takeovers, and ruthless individuals asset-stripping

well-loved high street names for personal gain, it’s nice to see an

independent retailer with such a long history continuing to do well.

The annuals may have ended, but this year’s crop are still on sale

in the book department of their Norwich department store: two

traditions going side by side into the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment